Music of the Spheres

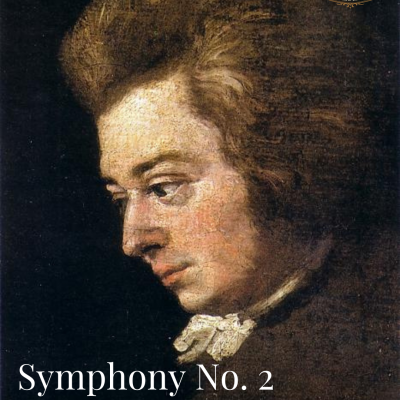

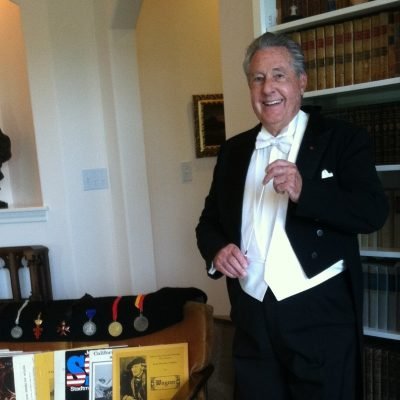

David Whitwell (1937–)

A 40-minute, 8-movement masterpiece for band by Dr. David Whitwell.

Date: 2013

Instrumentation: Concert Band

Duration: 40:00

Level: 4

https://soundcloud.com/user-861521360/sets/whitwell-music-of-the-spheres-2013

An ancient Egyptian hymn to the god Hathor suggests that some form of the concept of “Music of the Spheres,” the notion that musical sounds are produced by the movements of the planets, was known in Egypt long before the beginning of European literature. One might assume the logic for such an idea would have proceeded something like this: [1] music tones are created by vibration, [2] vibration is caused by movement, hence [3] the movement of the planets must ipso facto create sound.

The first important ancient writer associated with the Music of the Spheres was Pythagoras (6th century BC), best known today for his having identified the ratios of the lower part of the overtone series. Having discovered these ratios, he is said to have concluded that these same ratios must be identical with the ratios of the distances between the then known planets as viewed from the earth, an idea which lost its credibility when it became known that everything rotated around the sun and not the earth. Nevertheless, due to philosophers’ desire to account for all natural things in a logical explanation, the notion that the overtone series might be related to the placements of the planets did result in music being included among the real sciences of the medieval Quadrivium, with astronomy, geometry and arithmetic.

However attractive this logic seemed to philosophers who discussed this topic during the thousand years following Pythagoras, the stumbling block was always the fact that one cannot hear this Music of the Spheres. Many early thinkers advanced reasons for this, as for example in the case of the great 17th century mathematician Marin Mersene in his monumental Harmonie universelle of 1636. He suggested that the fact that we had become accustomed to this music from the time of being in the wombs of our mothers caused the very continuous nature of the music to be unnoticeable. Or, then again, perhaps it is because this music is too far from us, too low, too high, or too great to be heard, as happens with certain other phenomena. We are, for example, unable to hear the sound or noise which ants and other little animals make when they walk, run, crawl, or fly, inasmuch as the sound is too little and too feeble.

Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) was the last important astronomer to take seriously the music of the spheres. One day, when teaching a geometry class in 1595, he was drawing on the blackboard a triangle inscribed within a circle, in the centre of which there was yet another circle, whereupon he experienced a sudden insight—it seemed to him that the ratio between these two circles was the same as that between the orbits of Saturn and Jupiter. This led to a long period of study in which he attempted to prove that the organization of the planets followed basic geometric figures. Then he realized that in his purely geometrical and mathematical explanations he had given no consideration to time. It was the realization that time must be a factor in planetary design which caused him to turn his attention to musical harmony (which also moves through time), eventually resulting in his Harmony of the Universe (1619).

A minority of important early thinkers, beginning with Aristotle, had immediately dismissed the entire idea of the Music of the Spheres as nonsense and after Kepler the subject has had little discussion. However the discovery in 2002 by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory that a black hole in the Perseus cluster produces a Bb, 57 octaves below middle C has reintroduced the subject. It is not the Music of the Spheres of old, but it raises once again fundamental questions of pitch, movement and time.

Music lovers today are familiar with The Planets by Gustav Holst, a magnificent cycle of compositions which attempt to give an actual physical or characteristic description of the individual planets as understood by Holst. This was not the goal of the present Music of the Spheres. In my case I wanted to compose music which expressed some of my own ideas of the planets, ideas often being mere feelings too indistinct to put into words. Since this subject was still very much a topic of discussion during the Renaissance and Baroque Periods, I decided it would be interesting to associate my feelings with early dances of those years.

David Whitwell

Austin, 2013