On the final day of my 2017 conducting tour of Italy I took advantage of a rare non-professional day to visit the famous medieval cathedral in Milano. As I was sitting in the nave enjoying a quiet moment of contemplation following a very full five weeks of conducting and teaching seminars, not to mention the time consumed by travel itself, I began to consider my fellow visitors to this great architectural marvel.

The plaza before this cathedral is always filled with hundreds of visitors to Milano and a great many of them stand in very long lines waiting to obtain a ticket to visit the cathedral and then in additional long lines to actually enter the church. Why, I began to wonder, are these hundreds of ordinary tourists, most of whom had probably not been in any church during the past months, willing to stand an hour or more in lines to see the inside of this cathedral? To be sure, the building is prominently featured in all tourist publications as one of the things to see in Milano, but is there anything else in Milano, save the famous painting by Leonardo, for which they would make this physical sacrifice?

Once inside the great expanse of this cathedral, excepting a few in prayer, these tourists, in their shorts and baseball caps, with cell-phones and other means of photography at hand, seemed to me to be noticeably lost. Most were walking without direction, looking left and right and appearing somewhat confused about what to admire. They were taking pictures of tombs and memorial stones of obscure, long forgotten archbishops, photos of the stained glass windows of course, but mostly taking pictures of themselves—documenting their presence in this famous tourist destination.

Taking into consideration the effort and sacrifice to actually get into the cathedral and the apparent confusion on many faces regarding what to do once they were inside, I began to contemplate on the question, “Why are they here?” What in some subconscious aspect of human nature draws them here? And what will they take away with them from having been here? On further reflection, it seems to me that there is something involved in human nature here from which it follows that perhaps the very same questions may be asked regarding the audiences who populate concerts of classical music.

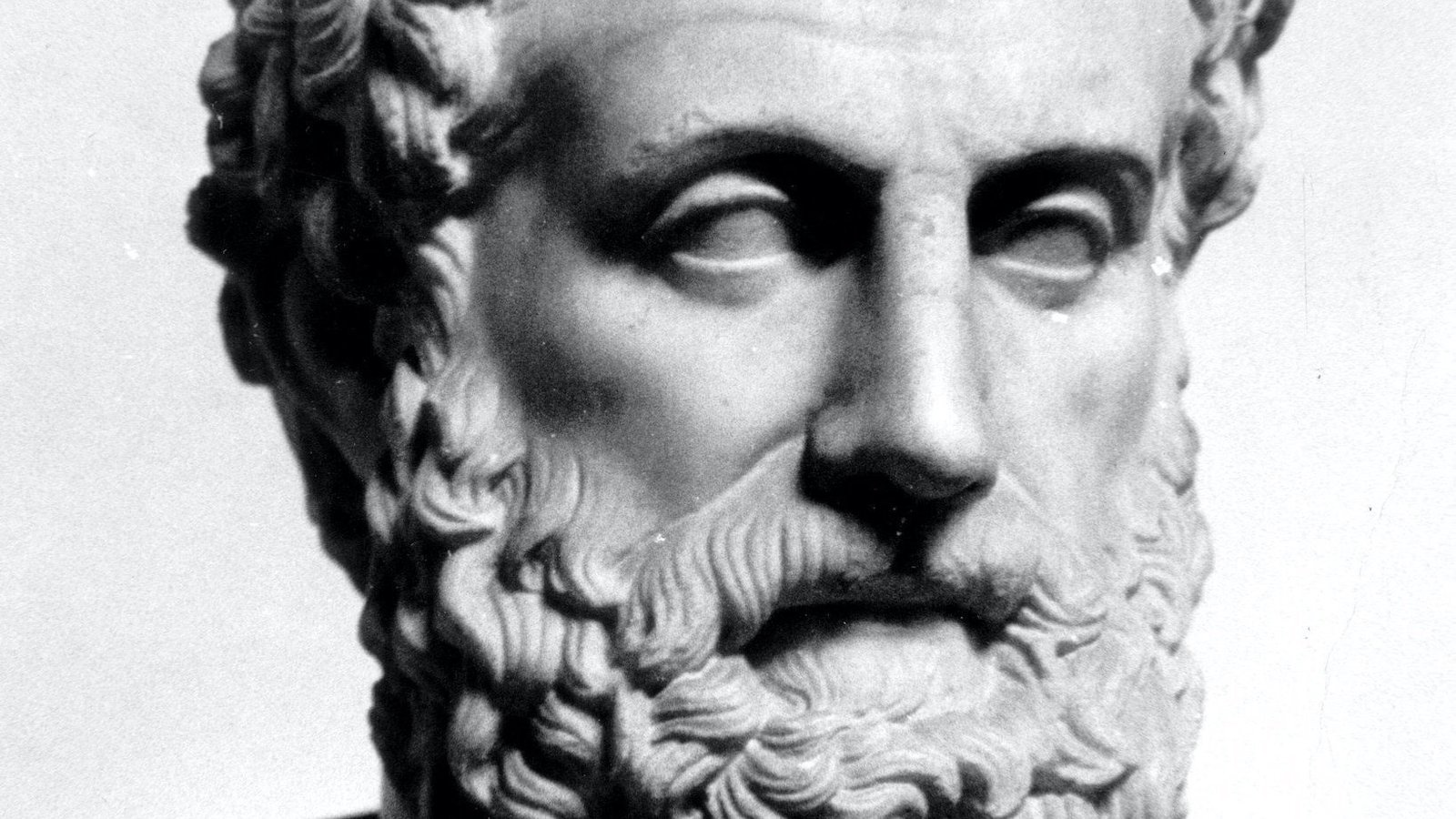

Whether from the perspective of science or philosophy, it is clear that we are a bicameral species. We have a rational side, which involves most of the common activities of life, and an experiential side, which involves only our own personal experiences, feelings and emotions and awareness of our senses. Almost all of education is designed for the rational side, and is, incidentally, entirely past tense. Because our experiential side is entirely personal in nature, and is the real present tense us, there is a kind of void with respect to the world of facts and data of which most of society depends. It is this void which causes a certain insecurity in one’s cognizance of his own spiritual life. Adding to this insecurity is the fact that our experiential side, the right hemisphere of our brain, is mute, it cannot write or speak. It is the consequence of this insecurity in our spiritual awareness which, I believe, is the origin of our unconscious need for contact with the spiritual world, including both music and religion. We are drawn instinctively to both music and religion in the need for experiencing an uplifting in our spiritual life. This need for uplifting the spiritual side of ourselves, as opposed to mere entertaining or pleasing ourselves, is what Aristotle recognized when he created the new branch of philosophy, Aesthetics.

It falls, therefore, to the choice of every conductor to be either an entertainer or a source of uplifting and enlightening the audience. It is this choice which I believe will determine the cultural identity of the Italian wind orchestra in the future. What does this mean in terms of the selection of the musical literature you set before your players and your public? We must begin with the recognition of two long accepted principles regarding aesthetic music, music which uplifts and enlightens the listener. First, there is no middle position. When the listener leaves the performance he will feel either entertained or enlightened. There can be variety in the programming, but there can be no doubt that in retrospect the listener will in the end feel having been entertained or having been enlightened. The second long accepted principle is based in part on the first; aesthetic music can have no purpose other than the direct communication with the listener’s feelings.

The question for band (wind orchestra) conductors concerned about the role of their medium in the society of the future is therefore whether they choose to entertain their audience or be a source of spiritual enlightenment. For those who wish to entertain their public they must face the fact that their choice will be in competition with the extraordinary variety in entertainment already offered the public. In my hotel room in Milano was a cable TV with a preset choice of 1,000 channels. Not all are yet filled, but the very prospect of the planning is staggering. And then there are sporting events, cinema and an endless list of other entertainment possibilities. Can the band compete with all this as an entertainment medium? Surely most conductors will foresee that being a source of spiritual enlightenment of the public is the greater contribution to their town and society at large.

Another very important consideration regarding the selection of musical literature for the wind orchestra is the spiritual growth and education of the conductor himself. The music we play is the greatest single contribution to our own growth. I recall hearing a beautiful recital by the great pianist Emanuel Ax during which the program of the music of Schubert was heard consisting of the most sensitive and free interpretation of phrases and cadences. In listening to this beautiful interpretation it occurred to me that the performance was not the result of the pianist’s formal education, or even the result of his own study as a student. Rather it was the music itself, the music of Schubert, which taught the pianist the musical sensitivity he communicated to the public. How much music in the band repertoire is capable of teaching us greater musicality? Very little I am afraid and so we must look for repertoire from which we also grow.

Finally, for the conductor who desires to enlighten his public, he must learn to also understand and communicate the non-rational content of the score, for obviously it is this which communicates with the audience. This entire subject is not taught in music schools whose sole curriculum is only the grammar of music. For example, in reference to a question about precise tempi Beethoven observed that “feeling has its own tempo.” In what academic music class is this discussed?

Because music schools teach only the grammar of music they lead the young conductor to believe his job is to present a faithful performance of what he sees and understands from what is on the page before him. But this is not the purpose of conducting; the purpose of conducting is to reproduce the music, not the notation. Consider the wonderful composition by Milhaud, his Suite Française. If one only studies the musical grammar on the page, chords, counterpoint, etc., one often ends up presenting to the audience only another of many pleasant “folk-song” compositions. But this is far removed from what the composer himself was thinking. He wrote that he was thinking of “war, destruction, cruelty, torture and murder”. In what theory or conducting class will we find this discussed?

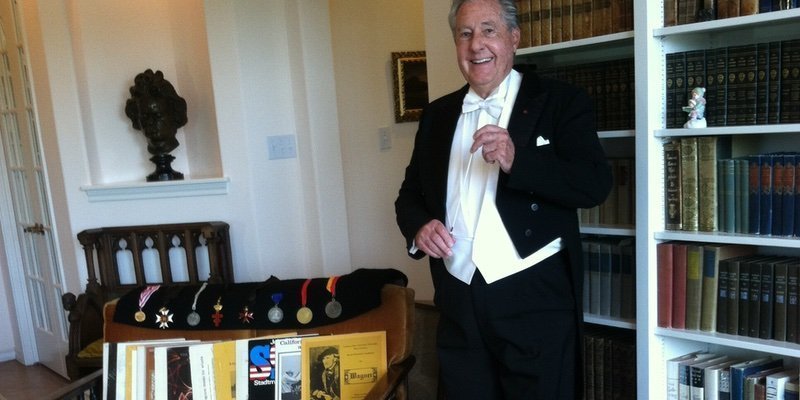

Copyright © 2017 David Whitwell