Music is a special language for communicating feeling.

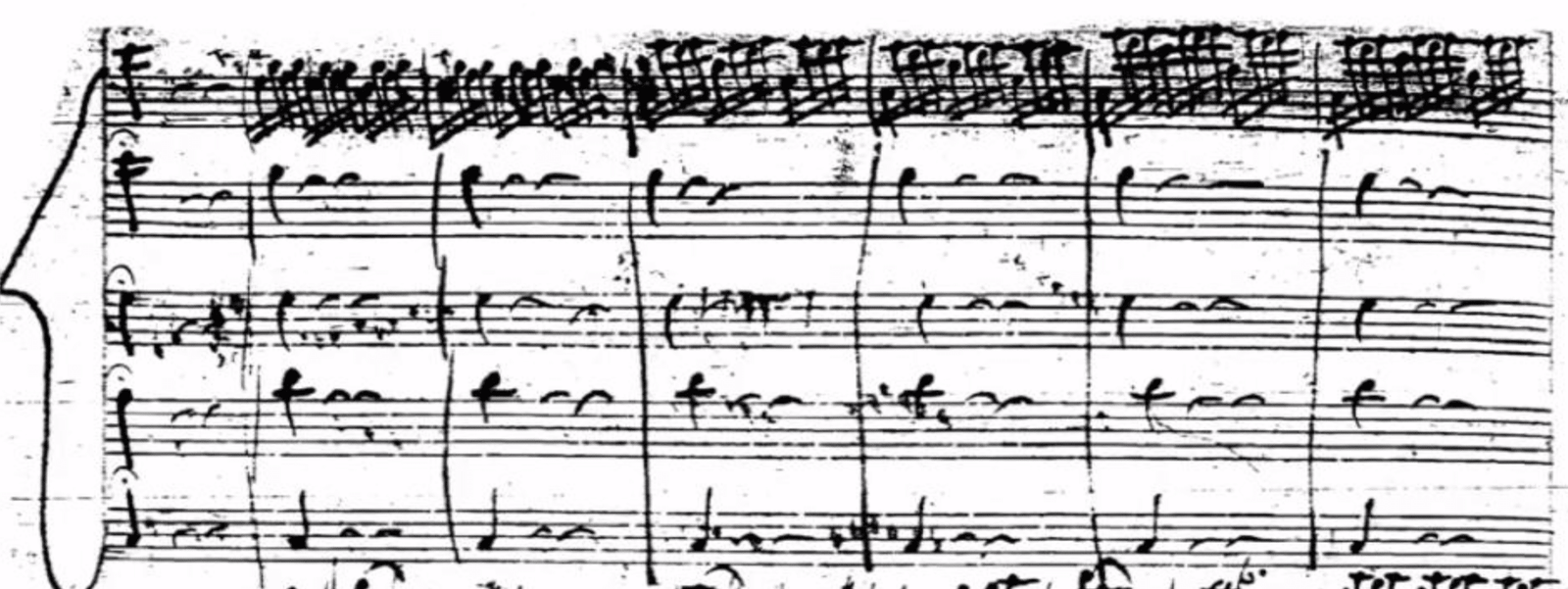

Your job as the conductor is to work out what the composer felt, not what they wrote. There is no music in a score. Only grammar.

Felix Weingartner says that the conductor who cannot take their eyes off the score, “is a mere time-beater, a bungler, with no pretension to the title of artist.”

The single biggest change you can make to your conducting to help the musicians express the emotions of the music is to memorize the score.

Is score memorization only for professional conductors?

Absolutely not. Score memorization improves everything you do in rehearsal and concerts, and is applicable to all grade levels of music, from beginner bands to professional ensembles.

Why should we memorize the score?

Every time we look down at the score, however briefly, three bad things happen:

- The line of communication with the musicians is broken.

- The conductor loses all facial expression because the left hemisphere of the brain takes over and goes into grammar-reading mode.

- The eye focuses on the exact bar/beat being played because of the vertical alignment of the music and the bar lines. The only way to know what is coming ahead is to know the music by memory.

How much detail do I need to memorize?

Consider the first two chords of Beethoven’s Third Symphony … Do we learn anything about the meaning of these chords or about how to conduct them by discovering they are E-flat major chords? Would we conduct them differently if they were F chords? Is our understanding of the meaning of these chords influenced by discovering which chord tone the third horn plays? … These kinds of details are the composer’s private business, not the conductor’s business and certainly not the business of the listener. (David Whitwell, The Art of Musical Conducting, 2nd edn (Austin: Whitwell Books, 2011), p. 132.)

To be able to say whether, in a diminished seventh chord, F-sharp–A–C–E-flat, voiced in twelve wind instruments, that the note of the third horn is C or E-flat may be very gratifying to the conductor’s ego, but it will hardly make a difference in the quality of his performance. (Peter Paul Fuchs, The Psychology of Conducting (New York: MCA, 1969), p. 27.)

These two quotes put my mind at ease when I first contemplated memorizing scores. You don’t need to know the minutia of a score to be able to conduct it from memory.

To conduct a concert from memory you need to know details of tempi, time changes and major entries, and most importantly, you need to know the feelings or emotion of each section of the music, so you can convey this to the musicians with your entire body.

To conduct a rehearsal from memory is harder and you’ll need a greater knowledge of detail. A more thorough knowledge of entries and who is playing what and when as well as a knowledge of rehearsal marks.

Guess what? You can already do it.

Imagine either of these two scenarios, both of which have happened to me more than once.

Scenario 1: you are in the middle of conducting a concert and all the lights go out, maybe from a storm—in my case it was a parent leaning against the light switch on the wall—twice!

You’re in the dark and can’t see. The players can squint and lean closer to their stands and they are carrying on. What do you do?

Scenario 2: You are conducting outdoors and a gust of wind blows your score off the music stand and out of reach.

The band are still happily playing, watching the panic-stricken look on your face. What do you do?

In both these cases I just kept going, and of course, the band didn’t stop, they didn’t fall apart, and I was forced to conduct the remainder of that piece from memory. What surprised me, after the initial shock, was that it was actually more enjoyable and the musical result was better. My eyes never left the musicians, because there was nothing else to look at, and so the musicians and I had far better non-verbal communication.

These situations, although forced on me, showed me that by concert time, I can already conduct from memory. The hardest part is not memorizing the major elements of the music. The hardest part is overcoming the fear to not open the score!

Where do I start?

Quick tip: Here is where I first started with trying to conduct from memory. Challenge yourself to do this. You have a score on your stand. Call for the players attention. Now, just before you are about to give the upbeat, DON’T LOOK DOWN. Trust yourself. You know how the first bar goes. Sing it in your head. Now, with the body language that reflects how you want that first note to be played, give the upbeat. Don’t take your eyes off the musicians.

This is a very simple idea, but it can have a great effect on the ensemble. Imagine if you are in the band, and just before the piece is to start the conductor looks down at the score. The musicians are thinking, “Do they not know how it goes? Is the first bar different today from the last ten times we’ve played it?” Everyone is capable of this simple introduction to score memorization. Before the upbeat, DON’T LOOK DOWN!

The Cheat’s Guide to Score Memorization

- Select the repertoire. Score memorization starts here. If you’re serious about choosing the best repertoire for your ensemble then you would make a short list of prospective works for the year ahead and you would listen to them several times while perusing the score, if possible. When you finally settle on your year’s repertoire you will have already listened to each work many times and would already know the major tempi and styles.

- This is the cheats guide, so most of your score memorization can be done on the podium and without significant time spent in study. For Grade 1 and 2 music, you’ll know the tempi, time signatures, and major entrances after a couple of rehearsals. For Grades 3 to 6 you will probably need to invest some time in learning the score outside of rehearsals.

- Use the score in rehearsal but progressively refer to it less and less over the course of the rehearsals. If running a section that has been previously worked on, make sure you don’t look down. By the time you get to the concert you won’t need to refer to the score at all.

- Music at Grade 4 level and above can have a multitude of time changes. Is it ok to use a score then? On the contrary, the more technically challenging the music is, especially the time changes, the more important it is to memorize the score. Without memorizing the score you will end up afraid to take your eyes from the score for fear of getting lost and you’ll be doing nothing more than beating time.

- Start simple. Play a march. No time changes. No tempo changes. It doesn’t matter if you aren’t expressive at all. Start the band. Stop the band. Don’t even open the score. Look at that! You just conducted your first piece from memory.

Peter Paul Fuchs, in The Psychology of Conducting, sums up score memorization perfectly:

The decision is not “to memorize or not to memorize,” but to conduct from memory with or without the use of a score. (Peter Paul Fuchs, The Psychology of Conducting (New York: MCA, 1969), p. 31.)

Good luck.