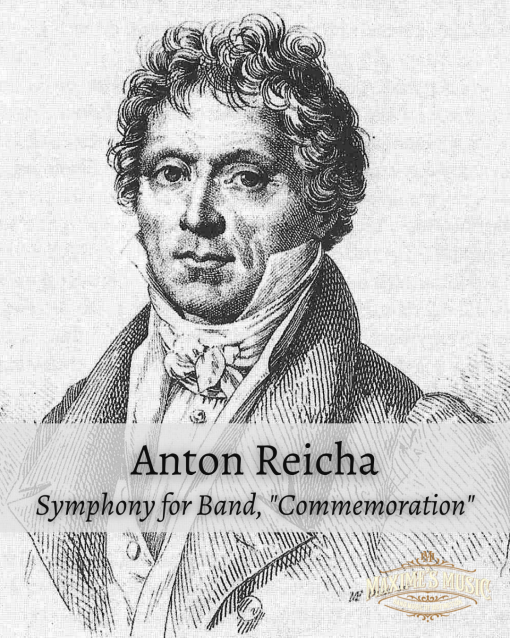

Symphony for Band

Anton Reicha (1770–1836)

Modern edition by David Whitwell (1937–)

Date: 1815

Instrumentation: Concert Band

Duration: 19:00

Level: 5

Notes on the Reicha Symphony

This Symphony is one of the great monuments of the repertoire for the wind band. To fully understand the unique nature of this score one must first recall the late 18th century tradition of the great public festivals in Paris during which a large wind band, composed by bringing together numerous smaller bands, played a central role. During the first of these festivals in 1790, which featured a Te Deum by Gossec for chorus and band, the powerful influence on the public made by a large mass of musicians in an outdoor environment caught everyone by surprise. The final organization of one of these large public festivals resulted in the Berlioz Symphony for Band.

So it was that in 1815 with the final fall of Napoleon and the consequent end of the long period of the Napoleonic Wars, which had been so expensive in lives and money, Anton Reicha, a gifted composer then living in Paris, anticipated that another one of these great festivals might be organized. It seems clear that his purpose, in 1815, was to create in advance a composition suitable for such a great outdoor performance. In the same spirit as Beethoven, who first dedicated his Third Symphony to Napoleon and then changed his mind and scratched out the dedication on the autograph score, Reicha apparently realized that a work dedicated to Napoleon would have a very brief performance life and so he outlined a much broader purpose. While the title on the autograph score reads, “Symphony without strings” (Harmonie complete ou Symphonie sans insts. à cordes), in his handwritten preface Reicha identifies his purpose,

This work is composed to commemorate: 1st, the memory of great exploits; 2nd, the death of heroes and great men; 3rd, to celebrate any important future event.

It was to make his Symphony practical, no matter how vast the open air space might be, that Reicha created a form based on the principle of the Baroque Concerto grosso. This explains the curious appearance of the autograph score, where one sees in normal musical notation a symphony for one wind band, but in the margins, expressed in a special numeric code, his directions where additional wind bands could enter and exit in the manner of the old 17th century concertato style. He makes this clear in a note in the score where he writes, “Cette Symphonie est Concertante.” In terms of the concerto grosso tradition it seems clear that Reicha considered the music in the score (music for one band) to be the concertino, the principal ensemble, while the other two bands represented by his marginal code were the ripieno, or the additional ensembles which join the concertino from time to time. This is what he refers to in his preface when he says the extra parts are for use in music performed in honor of France (Les parties detaches de la musique en l’honneur de la Nation française.)

The autograph score of this Symphony for Band has one more note in the hand of Reicha which is of considerable interest and curiosity. But first it is necessary to make two brief quotations from his autobiography.

I have never been interested in writing for the popular demand. To enlighten the public has been my aim; not to amuse it … Many of my works have never been heard because of my aversion to seeking performances … I counted the time spent in such efforts as lost, and preferred to remain at my desk …

It is impossible to discuss my complete works here. More than a hundred have been published; about sixty are still in manuscript. Among the latter will be found my finest efforts …

It is known that he kept some of his “finest efforts” in a trunk. All this is important as background for one additional note in his autograph score. He says the score of this symphony for band is found in a collection of scores (Catalogue Nr. 1 Partition) together with the rest of the volumes of band music in code (et il y a dans le meme volumes des Sceruirs d’harmonie). Taken with the above quotations, one is tempted to think that perhaps Reicha, who had a local reputation for his interest in mathematics, had further works for band abbreviated in some kind of code similar to the one used in this Symphony. I believe whatever he was referring to remains a complete mystery.

In his autograph preface Reicha also makes interesting comments about acoustics and says the performance must be assigned to a good conductor, all of which are very rare comments for 1815. He also adds,

It is imperative to use the exact number of instruments mentioned in the score, otherwise the work would not sound as effectively. These instruments are: 3 piccolos, 6 oboes, 6 clarinets, 6 horns, 6 bassoons, 6 trumpets, 3 double-basses, 6 army drums and 4 small field-guns.

He amends this to give approval for contrabassoons as an alternative to the string basses. The instrumentation he gives above is for the principal band with two additional “ripieno” bands. The instrumentation of the primary band alone, the only parts given actual musical notation, is piccolo, pairs of oboes, clarinets, horns, bassoons, and trumpets, plus bass [string bass or contra-bassoon].

The question remains, how does one perform this magnificent music today? If one decides to perform the original version, as given above, then one encounters several difficult problems. First, one has in hand the only score in 600 years of original band repertoire which requires nine separate bassoon parts! One significant challenge is finding three contrabassoons. When I performed the original version in 1974 I used one my university owned and the one owned by the LA Philharmonic, but the search for a third instrument in good condition was surprisingly difficult. Also, in my 1974 performance, I found that a considerable distance between these three bands was necessary in order for the listener to understand that they were in fact separate ensembles. That is, since all three bands play the same notes in unison, the ear tends not to sort things out into three divisions. As a result, for a good effect from the audience perspective a very large stage is required, something rarely found in most universities or civic institutions.

In my desire to make this beautiful music available to future students, I next tried to score the work for one modern band, but having the “extra” bands identified through dissimilar instrumentation. This, to my ear, had even a worse result, for it sounded like a composition for band with an extra jazz band and brass band.

Finally, in recognition of the fact that the composer heard in his mind and wrote down actual music for one band, the extra bands written in code, again, being given only doubling parts in unison, and, as the reader has seen above, described first a Symphony without strings and separately a work which could be used “in honor of France,” I began to think of this symphony as one for only one band. This for me was the key, for I realized it was still possible to make an edition for modern band of just the principal part which could result in a performance that still sounded like a work written in 1815, still sounded like Reicha and captured throughout his beautiful music.

Finally, bound together with the three original movements of the Symphony is a works for the same instrumentation, but minus the flutes, called a funèbre marche.

It is not clear whether Reicha expected this work to be a movement in the symphony, for he comments “It was principally for the army that I composed this marche funèbre, which may be performed alone.” It is a beautiful and noble work and I accept it as part of the symphony because it has the same instrumentation, even the four cannons. The missing flutes probably reflects the fact that the army did not use the flute, but rather the fife. Finally because he allows that “it can be performed alone” an alternative is assumed, and that must be the symphony with which it is bound.

Performance Notes

This edition has been prepared in such a way that one can use either the 4 cannons, which is a remarkable effect if one has one timpani in each of the four corners of the hall, or alternatively by one timpani player on stage.

For the long drum roll in the second movement, Reicha suggests placing that player behind the audience if possible.