Considerations for the future of wind bands, part 1

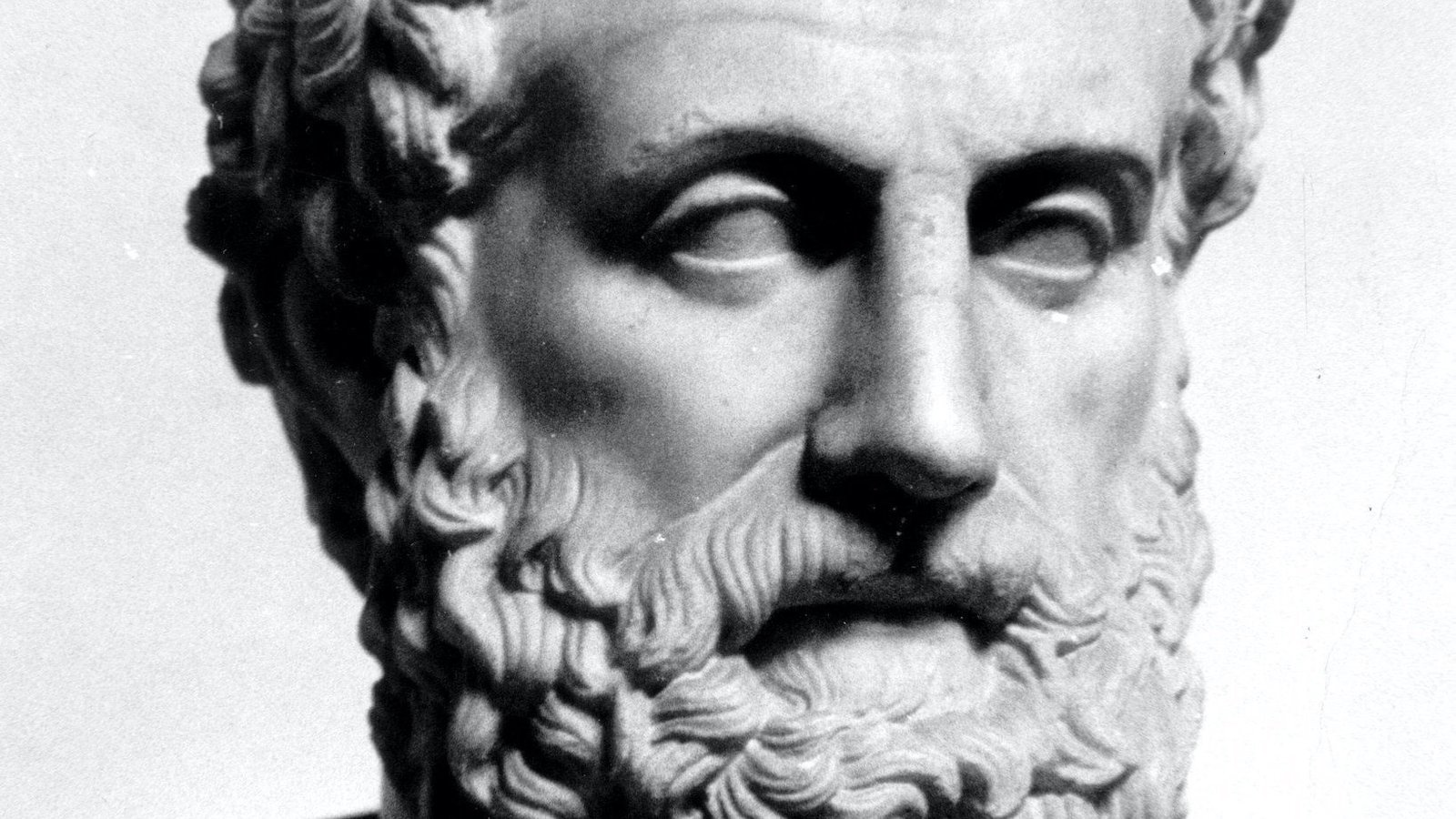

Aristotle was the first to explain the fact that the words we speak are only symbols of something else. When we speak the word “dog,” it is a symbol for a four-legged animal; the spoken word “dog” is not an actual dog. The art of writing came much more recently than speech and Aristotle pointed out that when we write “dog” it is only a symbol of the spoken word, “dog,” which in turn is only a symbol of the actual animal. Thus the real point he made is that when we write “dog” we are two generations away from the real thing.

This great principle has been lost when we teach music. We have forgotten that the notation on paper is not music; it is only a written grammatical symbol of real music. The fundamental problem that follows here is that we tend to teach students and adult players to read music, which carries the impression that music exists for the eye. But this is clearly wrong, music is for the ear! The way we teach makes no more logic than taking the student to an art museum to smell some paintings!

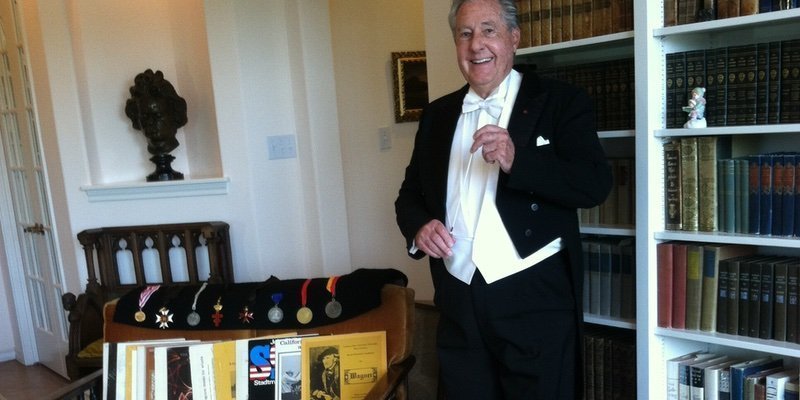

In addition, a very important aspect comes into play due to the bicameral nature of our brain. Written words are a form of data found in the left hemisphere of the brain; they can be found in a dictionary and have identical general meaning for all readers. Thus when a poet writes just the word “dog” he is using only the general dictionary meaning of “dog.” But on hearing the word “dog” the individual listener, or reader, will immediately think of some dog he has known from his own experience and not the one the author had in mind. If it is important to the poet to create the impression of a specific dog he has in mind then he must add an extensive additional description to override the listener’s personal experience to communicate that what he has in mind is a brown dog, with white feet, and is small and friendly, etc. Wagner has pointed out that this is the same thing which happens in the performance of music. The composer, through the performance on stage, communicates only a general, quintessence, of an emotion, such as “sad,” but when the music goes out into the hall each listener sifts this through their own experience and thus each listener hears something different and personal.

This has been one of the most important discoveries of the past century of bicameral brain research: that when we write the words we use reflect only a generic form of agreed-upon language and are nothing but data. But, whenever we speak the right hemisphere of the brain adds to what is heard the elements of color and emphasis which create meaning for the words. For example, one can utter as mere words, spoken in a flat voice, “I love you.” The result is heard only as data and communicates no specific meaning to the listener. But if one emphasizes either the second or third word, or both at once, suddenly there is meaning. [Emphasizing only the first word might lead to an unfortunate result.]

This great genetic role of the right hemisphere is also what creates meaning in music and is the basis of interpretation and what we mean by “musicality” in performance.